Part 1 A Town of Two Halves

A Georgian Ball

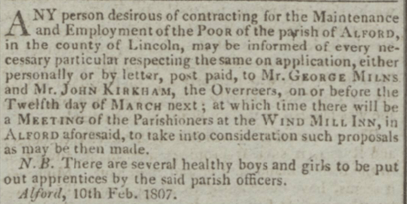

In October 1785 local society gathered at the Windmill Inn for the widely anticipated Ball and Card Assembly. Alford Market Place must have been a glorious sight as the coaches arrived, pulling up outside the inn for the occupants to alight before moving away to await the return journey. Stewards ensured that only those who qualified could gain entry.

A contemporary report reveals the scenes inside the Assembly Rooms.

Here a lady puffing and powdering in one end of the gallery, only concealed by clouds of the frizeurs raising; at the other [end] two or three tailors assembled measuring gentlemen for some article of their dress they had unfortunately overlooked, with a thousand other laughable circumstances attending the hurry of mantuamakers, milliners, tailors and hair dressers, running about in confusion.

The greatest part of the company being assembled in two rooms … the ballroom at the appointed hour was thrown open, instantly the orchestra played God Save the King with a solemnity that added force to the novel and delightful sensations of surprise felt and expressed by the company.

The organisers were well acquainted with the grand regency balls in London, Brighton and elsewhere, no effort had been spared on the Alford décor. Scenes of a temple and ornamental pillars created the appearance of a semi circular recess. The area surrounding the dance floor was adorned with … wreaths of flowers hung in rich festoons around the cornice … orange roses and carnations were combined and tied up with large pink bows of textile that appeared like broad ribbons. The wax lights were numerous and brilliant flowing over the pediment and chimney piece, over each of the chandeliers was a fixt wheel bound with leaves and flowers. The most enchanting view of all was declared to be that of the orchestra. On a raised platform each musician sat amidst pillars connected by arches of evergreens and flowers.

The long and detailed report continues to describe the assembly, there were card tables in profusion; upon opening the Minuets began immediately; country dancing followed, tea was served at 11pm, then dancing and cards continued until the company of around 250 people broke up at 8am. The whole thing was declared a great success, the writer suggesting it was as well managed as those in France “They do manage these matters much better in France and we do well to imitate a little”, he would shortly have grounds to revise that opinion.

Closer inspection reveals that even a prestigious event such as this ball was closely connected to the issues fuelling Free Trade.

The premise of the Ball had been to promote Lincolnshire Stuff, (textiles created from scratch in Lincolnshire) and to support the Schools of Industry set up locally to train the children of the poor to spin and weave. A ban on wool exports, to appease English weavers, ensured a glut of wool, low prices for farmers and led to a flourishing trade in illicit exports,particularly as English wool was much sought after on the continent. The assembly was the brainchild of the Reverend Gideon Bouyer of Willoughby and Theddlethorpe, who was very well placed to understand the suffering of the poor and the temptation of the activities along the coast.

The Windmill Inn housed not only the Assembly Rooms but also the Excise office where the infamous Thomas Paine had been employed in August 1764 to watch the Smugglers of Alford. Paine had been dismissed the following year, several others had followed, all equally eager to escape the despised role.

In 1789 the Excise Board embarked on a Country wide inspection of officer workloads, seeking to reduce costs and aiming to remove six hundred men by closing small offices. Despite the circumstances behind their investigations, Excise Board inspectors agreed that the situation in Alford demanded the appointment of an additional officer.

In the September of 1789, the press announced that, under the Patroness of Lady Banks, the Lincolnshire Stuff Ball would now be held in the Assembly Rooms, above the hill, in Lincoln. Those who had subscribed believing it would be in Alford were given 24 hours to withdraw. The ball did not return to Alford, with turmoil at home and revolution in France the privileged chose to stay away from the countryside.

As the coaches left Alford on that cold November morning after the first ball, the tired dancers are unlikely to have paid much attention to their surroundings. The recently burnt out building of the George Inn, home to cockfights on racing days, may have drawn some comment but little else would have been of interest. Possibly the ladies were full of chatter about the night before, the men considering the beauties with whom they danced, or broodily regretting staying too long at the card tables.

Some in the town would have watched the coaches depart with more than a passing interest. Those ruthless characters who got their hands dirty, who preferred to work in the shadows, they were the link between coast and country, they were the men who buried the bodies.

The Dead Do Not Stay Buried

In the late 1800s, when the dead began to make their presence known, widespread reporting in local publications provoked a lot of debate. The remains were seen as confirmation of tales from previous years and the whispers handed down the generations began to be shared more widely. The same anecdotes were frequently resurrected by newspapers in the twentieth century, forming the foundation of many stories which remain in circulation today.

Part 2 Dead Men Tell No Tales

Alford: Smugglers Tales

The first discovery of a number of skeletons took place in July 1868 following the demolition of Buffham’s ancient thatched cottages in a section of the Market Place, known as the Butter Market. The ground was disturbed in preparation for the foundations of a new brick building and the remains of four skeletons were discovered just below the surface.

A brief newspaper report concluded that the state of decay was too advanced, and the remains too old, to form a judgement as to how the unfortunate victims met their end but “the curious place of interment suggests … scenes of violence were enacted at this singular spot” . Within a week the number of skeletons found had risen to ten, buried in various positions, one appearing to have been thrust into a hole as the remains were upright. The report notes that speculation in the town was rife as to the true story of the incident but unfortunately those stories were not reported.

Ten years later another of the town’s old inns was demolished, this time it was a stable that revealed its gruesome secrets. Murderous tales of old smuggling days began to be shared in print.

The demolition of the Old Stag’s Head public house in 1878 revealed two skeletons a foot below the surface of the stable floor The Hornes, as the locals called it, faced onto West St. The stables were situated to the rear in Park Road. The first skeleton had been laid out as expected with hands crossed but, upon lifting, it was discovered that a large portion of the back of the skull was missing. The second skeleton was buried below the first with far less care These stables had been erected in the early 1800s, reportedly the position of the remains led to the conclusion that they could only have been placed there after the completion of the building, although many years prior to their discovery. Further excavations discovered four more skeletons prompting a larger report on the incident.

Martin Wilkinson had been the licensee of the Stag’s Head from 1803 to 1807 his son, Hurdman Wilkinson, was keen to share the tales he had grown up with and probably sought to defend his father too.

The story he recounted to the press was swiftly reported:

… the smuggling of gin from Holland was extensively carried out at the coast in the early part of the century, and at times the illicit traffic led to fearful scenes. One Autumn afternoon, says Mr Wilkinson, five carts of contraband hollands were driven into the Hornes yard. The smugglers [Dutchmen] disposed of one lot before sunset and the remainder was taken on to the Red Lion yard where it soon found buyers. The next day the Captain and mate of the smugglers craft returned to Alford to receive payment from their old customers. Settlement [took place] in his father’s bar, and then the men left to go to the Red Lion on a similar errand. From that hour nothing was ever heard of the Captain or the mate, who were relations, and owned the vessel in which they traded. At about the same time a commercial traveller left Spilsby for Alford, [he subsequently disappeared] and no trace of him could be found. Bow Street officers made strict enquiries , and also searched the Hornes premises and Buffham’s Inn (now Mrs Green’s, chemist) in the Market Place. Inquiries for missing men were made by similar officers more than once subsequently, and always without success. Some years ago we recorded the discovery of some human skeletons on the site of Buffham’s—one under the hearthstone and one built into a wall in an erect position. Stamford Mercury Nov. 1878.

Once captured in print the anecdotes recounted by Mr Wilkinson continued to be retold by the newspapers whenever other skeletons were found. Further findings were in 1881 at Bourne Place, close to a derelict hut rumoured to be haunted, and then in 1949, close to Buffham’s Cottages original site, by telephone engineers. In 1881, when the two skeletons were found at Bourne Place, Mr Wilkinson wrote to the newspaper once more with details of his story, emphasising that it had been related to him by his father and grandfather.

The find at Bourne Place revealed two bodies pitched into a hole, the lack of buttons and leather convinced Mr Wilkinson that all clothing had been removed, he felt certain that these were the two Dutchmen who disappeared. Family members had been to Alford looking for them at the time.

There are a lot more tales around, most have been passed down the generations and they are not [yet] backed up by documentation. Common stories include: tunnels from the Red Lion under the church to the George Inn, skeletons discovered at the Red Lion, and casks of liquor discovered upon the removal of the old toll bar to name but a few. In the early twentieth century the discovery of gold coins under a pantry floor in East Street was also believed to be connected to smuggling, the coins were dated between 1734 and 1828.

Although many Alfordians loved the tales others, who were working hard to improve the town, were keen to put the past behind them. An article in 1882 ignited a war of words about Alford in “ the olden days”. Retired writer and publisher, Robert Roberts of Boston, openly criticised 1830’s Alford as a “vulgar ignorant little town full of poachers and smugglers”

Understandably Mr Robert’s comments were met with an outpouring of anger and he was forced to answer his critics with more details:

I have been in Alford hundreds of times, and have often passed the “haunted house” at Bilsby – a fine old place, shut up because “Theer waur a boggle in it” I could tell [you] about Tothby Hall, Thoresthorpe, Thurlby Grange, and the other big farm houses round; also a good deal about the people who lived there. “No, smugglers and poachers !” What about the Alford South End gang who shot one of Mr Christopher’s keepers dead, about two miles out of Alford ? and what about Louth poulterers who used to fetch cartloads of hares and pheasants away at once? These things were notorious .

I, many times, passed the house of a family of smugglers between Alford and the sea, about thirty-five years ago. There was a father with several sons, all of whom got their living by smuggling. They had no other occupation; they dressed as well ,and spent as much money, as any people in those parts. They owned at least one vessel engaged in the trade. Everybody knew it. Why were they not caught? Because the whole countryside sympathised with them. An informer would have run a chance of being shot as dead as the Alford poachers shot the gamekeeper. I have heard many curious tales from the farmers – how they used to lie still at night when they heard smugglers fetch their horses out of the stables to lead away the cargoes, and how they used to find kegs of spirits in the morning put among the straw as recompense for the use of the animals. Some of them used to boast that they got all their spirits for “nowt”. On a dark night, suitable for running cargo, these farmers would send their household to bed earlier than usual, that the coast might be clear for the horses to be fetched. No doubt many of their men went with their teams. R.R. Boston 1882

The war of words regarding Alford’s past continued for some time but the above comments were never addressed directly. There are many, tales which will never be proved but seemingly smuggling was rife, and clearly the skeletons pointed to murderous activity but were the two really connected ?

The tales of Hurdman Wilkinson and Robert Roberts provide some very basic, unsubstantiated, information from the 1800s. They seem like a good place to start in a search for the truth.

Part 3 The Lincolnshire Coast

18th Century Smuggling

18th Century levels of smuggling were astounding. War is a costly business, near continual wars throughout this period led to high taxation as the authorities needed to buy weapons and build ships. More men were needed to fight for their country, pressure to recruit was high. As smugglers worked to avoid taxation the legislation increased in a bid to stop them.

Customs and Excise – separate authorities in the early years – officials were supported by men from the Admiralty and militias. Illicit wool exporters risked the gallows. Kent and Sussex were home to the most notorious and brutal gangs of smugglers,their networks were orchestrated by wealthy London financiers hiding in the shadows. In Lincolnshire the same set up applied, smaller in scale but men of money and power were embroiled in the schemes to avoid the King’s Customs and many were connected to the London networks.

Fractured Government authority delayed decision making and undermined support for the officials working to stop smuggling on the front lines ( the prevention officers). By contrast Government documents reveal successful collaborations between the widespread smuggling networks opposing them. The inhabitants of coastal villages, large ports, and different nations worked as a team to bring the goods in. For example, in 1728, authorities gained 120 pounds income from the sale of a seized vessel. Among the culprits caught in the illicit venture were Anthony Royston of Rotterdam (the Master), Charles Parks of Marshchapel, Nicholas Taylor of Hull ( beer brewer) and James Wright (Mariner).

Foreign Vessels on our shores

In December 1729 Customs’ officials published a report into “The manner of carrying on frauds by the smugglers”. The raft of paperwork contained letters from Customs’ officers at Saltfleet, Anderby and Wainfleet, who reported to Captain John Jewell at Boston. Jewell was the commander of the Customs’ sloop covering the area from the Humber to the Wash, his superiors subsequently reported to the London board at Thames Street.

Throughout the Summer of 1729 French Snows were sitting off the Lincolnshire Coast. Two vessels, each carrying about 30 men with 8 guns, were lying between Saltfleet and Skegness. They were sending goods ashore accompanied by 12 or 14 men armed with pistols and swords. These men would sell brandy and guard their customers into the countryside, threatening to shoot any officer that opposed them. The same vessels were also carrying away wool. Captain Jewell was told that if he opposed them he would be captured, along with his sloop, and taken to France. Mr Jewell reported that … the “country people” are terrified of these men and dare not assist the officers, in short “the French are masters of the coast.”

Signed affadavits from Mr William Stonebanks of Mablethorpe (labourer) and Francis Willerton of Theddlethorpe (gentleman) confirmed that vessels lay off Sutton along with a 24 gun French Ship off Mablethorpe. Armed men were sent ashore offering to sell brandy, cards, prunes and scissors. Captain Edwards of Hull captured one French vessel along with 400 half anchors of Brandy, the crew had provided good information on French operation in Calais.

Four merchants at Calais were fitting out around ten armed vessels of about 40 to 60 tons, which their suppliers then stocked with brandy at their own risk, captured cargoes brought no return. The Snows moved to the English coast remaining within around eight leagues (24 miles) of each other to provide assistance. Another four merchants fitted out two smaller vessels of 30 to 40 tons. They also moved to the English coast to sell contraband but their sailors were paid in brandy as soon as the sales target had been reached. The methods of this outfit were believed to create more violent men as they were expected to resist the King’s men, failure to do so resulted in their immediate discharge.

Customs Commissioners from Thames Street, emphasised that the French vessels were in all manner superior to the English defence. They sought deputations to empower his majesty’s ships (customs vessels) to seize prohibited goods and condemn captured vessels. 49,000 half anchors (245,000 gallons ) of brandy were sold by the French on the Lincolnshire coast annually, in addition to the Dutch doggers who were also great traders. The report concluded that the English needed two 20 gun ships to have any chance of suppressing them. It was 5 years later in 1734 when HM Ship “The Fly” was commissioned to cruise between Flamborough and Yarmouth to prevent the exportation of wool from Lincolnshire and goods being run from France.

Captain Jewell: A Villain or a Coward ?

Custom House spies on the continent reported the loading of illegal cargoes. Detailed information on these and other coastal runs heading for Lincolnshire were passed to Boston but the resulting seizures were pitiful. Boston officers seemed reluctant to be proactive, merely reporting witness interviews taken after landings had occurred. The London solicitor judged the reports corrupt or inconclusive but commissioners knew that large business was being done.

Now under scrutiny Captain Jewell was criticised by the board and accused of making few seizures of minimal value. Boston officials provided affadavits accusing Jewell of embezzling contraband. Captain Jewell was relieved of his command until he produced his own affadavit stating that he had been fired upon when boarding a smuggling sloop; he was quietly reinstated. Further enquiries resulted in reports that Captain Jewell stayed too long ashore, however, Jewell asserted that on the exposed Lincolnshire coast the weather was so rough that it was frequently unsafe to put to sea. His sloop also needed extensive and expensive repairs once a quarter.

In 1735 Boston Collectors were instructed to establish the course taken overland when moving goods from Lincolnshire to London, a troop of dragoons were provided to assist. Operations on the Lincolnshire coast were not restricted to local supply lines.

The following year Thames St. reported to Boston that 3 collier ships were known to have discharged their cargoes and then taken on goods for running, overstowing them with ballast. 20 smuggling galleys each carrying ten men from Kent and Sussex plus five other vessels were all bound for the Lincolnshire coast. In turn Boston notified the board that large runs were being made by armed smugglers. Two sloops were provided by the Admiralty to assist. Captain Jewell had an opportunity to impress his superiors; he immediately began repairs on his vessel, even failing to provide his crew with a watching brief, earning another reprimand.

A mass of detail flowed from London to Boston: English Baltic Traders were moving goods from China to Sweden then running them on the Lincolnshire Coast; a boat was being built in London specifically adapted for running goods, it was to be carried on a laden sloop and used to run goods ashore. List upon list of information regarding goods to be run onto the Lincolnshire coast was provided, large seizures should have been the result but few materialised. Similarly prevention of illicit wool exports were also scarce despite immense wool yields in the County. Bizarrely Jewell still remained in post. In 1740 his repair bills were subject to scrutiny once more. The board’s response was incredulity:

It must be some extraordinary accident which the Captain has not mentioned that could occasion such large bills in so short a time after the sloop being rebuilt. In 1739 she cost the Crown £(l)142 7s a very large sum for so small a vessel and so soon after to require £(l)92 4s 6d for repairs only. They questioned a long list of bills including £(l) 10 charged for sails twice, their response concluded that … as much labour and materials have been charged for one and a half years wear and tear as would almost build the vessel.

Jewell was directed to make his bill more reasonable, he dropped one item and got his money. John Jewell would remain in post for another two years, he then applied for a further grant to repair his sloop. An expert assessor arrived to find him ashore and the vessel requiring no maintenance, he was ordered to put to sea but refused on the grounds that the weather was unsuitable. Captain Jewell was finally dismissed.

As Jewell’s story demonstrates prevention authorities faced adversaries within their ranks, as well as smugglers at home and abroad. These reports focused on the problems with the French Snows but others confirm considerable issues with Dutch Doggers along the Lincolnshire Coast throughout the 18th Century and into the 19th. In particular local newspaper reports from the 1780s confirm that armed foreign vessels continued to plague the whole of the East Coast for the purpose of smuggling.

Hurdman Wilkinson’s stories of Dutchmen selling liquor to Alford inns appear to have substance.

Part 4 Coast to Country

A Matter of Transport

Throughout the 18th Century legislation to support the prevention of smuggling burgeoned, primarily targeting those landing and transporting the goods. Incentives offered leniency and pardons to those who informed. This escalated the violence among criminal gangs involved in the trade as an informer could walk free by giving up his fellow smugglers to a potential death sentence or, if they were able seafaring men, being pressed for the Navy.

As Captain Jewell repaired his boat, a smuggler named Garrett in Lincoln gaol began to provide a startling amount of information. He first implicated a number of people along the Lincolnshire coast but then began demanding money (ten guineas) to provide further details. A London solicitor, acting for the Customs’ Board, rejected the offer but numerous prosecutions along the coast were undertaken on Garrett’s information including:

Bancroft (tailor) of Nth Somercotes & Oliver (mariner) of Theddlethorpe unshipped 300 pounds of tea & 150 gallons brandy.

Hubbard (mariner) of North Somercotes was named as involved in the above.

Bell (mariner) No Location- [likely Theddlethorpe] unshipped 2,000 pounds of tea.

Three sloops were also declared seizable when found, including that of Richard Burleigh, Captain of the Thunderbolt. Burleigh was a notorious smuggler previously imprisoned in Dover Castle for the murder of John Wood, a Customs officer at Newhaven. Burleigh had escaped in March 1737 and was known to be on the Lincolnshire coast. Garrett continued to name others along the East Coast, offering details on “two men of fortune and estate” who had recently unshipped 1600 pounds of tea, this time he requested twenty guineas and was again refused.

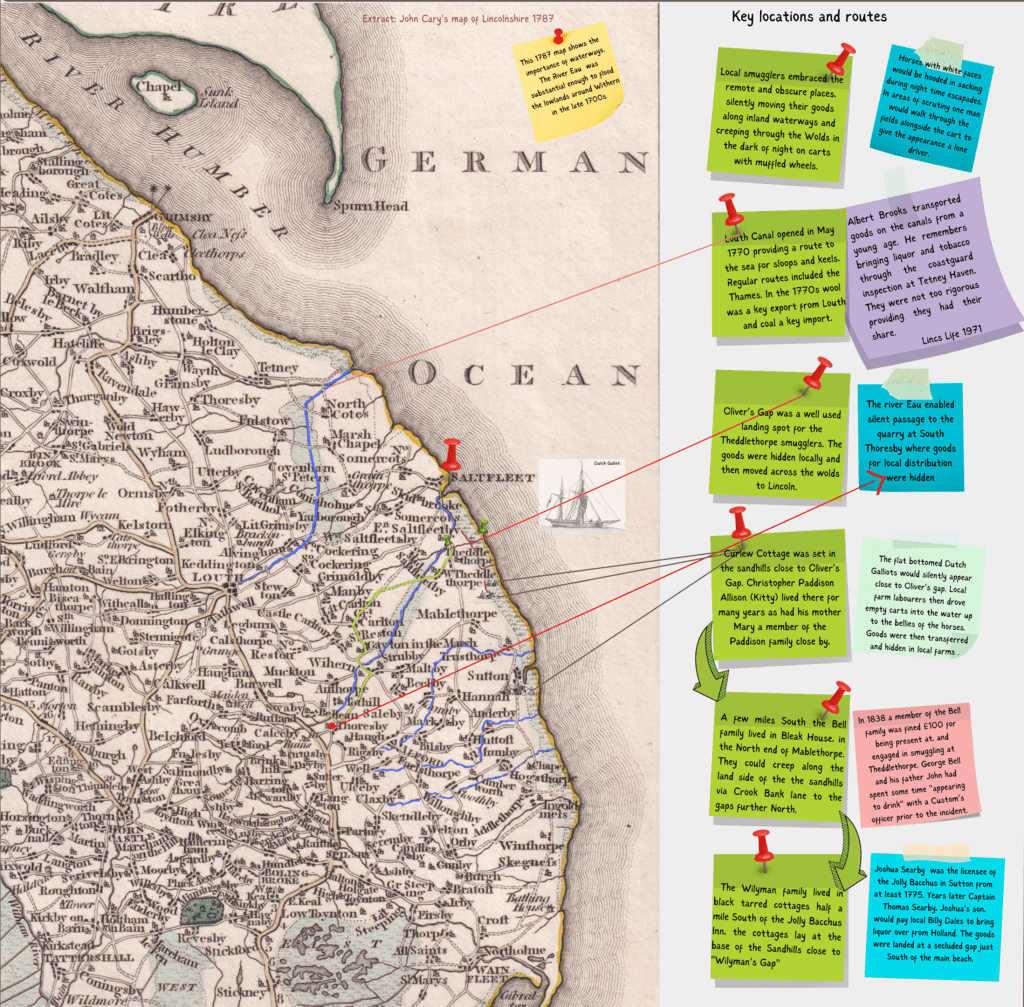

The Bell and Oliver families were renowned along the Theddlethorpe coast across the generations. These seafaring families landed their goods via the “gaps” in the sand dunes using horses and carts to transport the contraband to safe houses and hiding places. The gaps became branded by their notorious users, Oliver’s gap lay close to Saltfleet Haven and ironically appeared on some Admiralty maps. Local mariners had been trading with the low countries for hundreds of years out of Saltfleet. In 1771 the Complete English Traveller descibed the harbour Saltfleet as … pleasantly situated on the German Ocean, formerly a place of some trade. It has still a harbour for shipping but it is suffered to fall to decay, there being no ships that use it above the ordinary size of lighters. However, trade continued for many years, the efficiencies of Dutch merchants grew. Warehouses were set up on the continent to receive English wool and provide specially packaged contraband, for ease of concealment and transportation, upon return. The Customs men were not the only problem the mariners faced.

The Press Gang

During the wars of the 18th century seafaring men were an important commodity to the Country. Press gangs operated in harbour towns throughout the Nation, using local men and physical persuasion to force mariners to do their bidding. Many merchant sailors returning home, including captives recently freed from French prisons, found themselves unwillingly serving in the Royal Navy. During Jewell’s suspension the crew of his sloop mutinied in his support, they were all immediately pressed for the Navy.

In May 1804 five men were sentenced to three months in Lincoln Gaol as ring leaders against the “Press Men” in Boston. An assembly of over 200 people had attacked the Press Gang with extreme violence, using bats and stones rendering some unconscious. The Judge observed that:

… those people who constituted what were called press gangs were involved in a service, the object of which was the protection and preservation of the Country. As long as it was necessary to have fleets and sailors for the defence of the realm, so long would it be necessary to have press gangs. The law allowed them and whoever interrupted them was guilty of a gross violation of the war.

By 1804 twenty seven year old Robert Button of Farlesthorpe had already fallen foul of the the press gang. At fifteen Robert began working at the Red Lion, Church street, in Alford, where he remained for a couple of years before going to sea aged eighteen seeking excitement. After three years serving on different merchant vessels Robert had seen enough, his indenture papers were lost and he quit life at sea. HIs decision proved to be short lived, strong armed back to sea by a press gang. It would be another three years before he would return to Alford, serving instead on a Man of War for the Navy. Poor law papers reveal that Robert Button was not the only mariner to have settled in Alford.

Robert Peelings from Partney had been bound by Parish officers as an apprentice to a cordwainer at the age of 8 in 1784. Officially tied until the age of 21 the young man had run away to sea aged 17. Robert served until he was discharged in 1805 having lost a leg, he was now an “out pensioner” of Chelsea. In 1814 at the age of 38 Robert Peelings was once again reliant on Parish officers for a place of settlement.

Keeping it in the family

courtesy of Rachel Morton

A few miles down the road another “out pensioner” of Chelsea, a soldier, returned to his birthplace at Belleau.

Daniel Paddison was the son of paupers William and Mary Paddison, he had worked as a labourer before joining the 5th Foot Regiment in 1803. Wounded by a musket shot in his right thigh at the Battle of Salamanca (1812) Daniel Paddison was finally discharged in 1816 at the age of 31.

In November 1821 Joseph Bland, a labourer from Belleau, was sentenced to transportation for 7 years for theft. Daniel Paddison was the victim, court papers record him as a labourer. The stolen items were a man’s coat, a woman’s great coat, a cotton hankerchief, cotton braces and cord breeches. Despite his injuries Daniel Paddison appears to have been able to supplement his pension and obtain items his peers coveted. In later years the musket ball wound would be cited as the cause of his death so hard manual work and the poor pay rates of a labourer seem unlikely to be the source of Daniel’s extra income. Family connections suggest an alternative income stream as his sisters had married into the smuggling families of Sutton in the Marsh.

Sarah Paddison married Robert Wilyman (b. 1784) in Belleau in 1815, with Daniel’s brother Richard as a witness at the wedding. Their son Robert Wilyman (b.1826) married Sarah Bell, daughter of Edward (Ned) Bell in 1849. The couple would go on to have sixteen children, eight of the nine boys were seafaring men.

Edward Bell of Bleak House, Mablethorpe, was the eldest son of fisherman John Bell of Theddlethorpe. Active in the years of deceipt and concealment, which followed the violence of the 18th Century, farmer Ned Bell gained notoriety with numerous mentions in 20th Century Publications.

The Wilyman family lived in black tarred cottages at the top of Church Lane in Sutton, close to Wilyman’s Gap.

A young curate, William Bompas, was a neighbour of the Wilyman’s, in his later years as a Bishop he would reminisce about his days living among Sutton’s smugglers.

In 1801 Thomas Frow, a well known Mablethorpe innkeeper of the time, was a witness at a Wilyman wedding.

The Jolly Bacchus

Daniel Paddison’s elder sister Jane had married Captain Thomas Searby in 1814, the landlord of the Jolly Bacchus in Sutton Le Marsh. The 17th century inn had been in the hands of his family since at least 1792. Thomas took over after many years at sea, remaining in his post until he died in September 1852 aged 74.

A few weeks later Joseph Mason and his wife Ellen left the Victoria Hotel in Alford to run the Jolly Bacchus, Ellen was Daniel Paddison’s daughter.

One 19th century travel writer who stayed at the inn makes a tongue in cheek reference to his night at the Jolly Tobaccos, also remarking on the men and horses working hard to unload a coal brig in the moonlight. These collier vessels which plied their trade along the coast line were frequently connected to smuggling having other goods hidden beneath the coal. Thomas Searby is also listed in some trade directories as a coal merchant. Some years later diary extracts were published from the diary of a young man who fell in with smugglers in Sutton in the 1840s; the rogues and drunkards the young man fell in with passed their time at the inn.

Influential wealthy families intermarried to protect their own interests, in the same manner the free traders cemented bonds of trust and kept their secrets safe. Marriage between the families ensured that Jane and Sarah Paddison were well protected from the interference of Parish officers. As Belleau sits on the route taken across the Wolds by those moving the contraband from Theddlethorpe to Lincoln, Daniel and Richard Paddison were quite literally in a position to help.

Part 5 Smuggling Times in Alford – The Taverns

Alford … a small but exceedingly neat little town with a brook running though it, but built in so remote and obscure a place that it is seldom visited by strangers nor does it contain so much as one public building that merits particular attention. Complete English Traveller 1771

A 1784 trade directory reveals that Alford had no less than three surgeons and at least two attorneys at law. Other publications from the time provide further information on premises central to the town including: tallow chandlers, milliners, grocers, drapers, shoe makers, coal merchants and a hop merchant. Numerous other trades operated throughout the area. The Market Place was a hive of industry as a place to live and work. The old buildings were comprised not only of shops and accomodation but also the warehousing and stabling facilities required. Advertisements relating to businesses for sale assured prospective buyers that Alford was an “improving town”.

Such descriptions of Alford make it hard to believe that there could have been an undercurrent of violence in the town, but publications of this type rarely provided an accurate portrayal of all aspects of a community. When presenting a publication for pleasure or promotion it would be inappropriate to mention the glaring deprivations of the poor, or to ponder the presence of 11 taverns in a town of just 188 families (1791). A real view of Alford in smuggling times requires a look at the taverns and the poor. Taverns first, not least because that is where the bodies were buried.

The Inn

In 18th century rural England the inn was the heart of the community, so much more than a place to eat and drink. A town with so many, in relation the inhabitants, clearly did enjoy visitors and the taverns were frequently a key aspect of their experience.

Alford played a central role when it came to livestock, including horses. Newspapers frequently mention the race days and they were clearly a draw for the town. Horses were inspected in allocated tavern yards before the races. Selected (subscribing) inns received deposits and formalised entries. On race days the inns hosted cockfighting in the mornings and assemblies in the evenings.

Long lists of men, emboldened by drink, signed the rolls to join the militia. While fairs brought good trade, dubious women and pick pockets to the town.

The taverns had an official capacity too, holding meetings for associations and the creditors of bankrupts along with auctions of all kinds. Inquests, Post Masters and Excise officers, all found their place at local inns.

The Inn keepers

The law required that to become a licensed innkeeper a bond must be provided, along with someone to vouch for the applicant’s good character. In reality records show that the majority of licensees provided surities for each other, most likely a situation arising from convenience as they all attended the quarter sessions on the same day, and for the same purpose.

As with the marriage records of the mariners, the documents reveal a familiar community among the licensees. Many stood surities for the same person over many years. When a landlord died his widow frequently continued as the licensee.

The most revealing documents are those of licensees who are new to the trade or the area, they frequently contain more genuine surities, a character reference is unlikely for someone unfamiliar. This is worth keeping in mind when looking at the Stag’s Head.

Failure to keep an orderly house would result in the suspension or denial of a license.

Keggy Buffham’s Beerhouse

The first skeletons to be found in numbers were at Buffhams beerhouse in 1868. Joseph Buffham was a glover and breeches maker who owned his premises and had traded in Alford Market Place for many years, initially with no mention of a beer house. The 1841 Census captures him, aged 70, with his daughter Elizabeth, aged 40, and her sister Maria, aged 35. No occupation is shown for the two women of the house. The earliest mention found (to date) of a Beer House in connection to the Buffhams is in Pigot’s 1841 directory. The presence of large numbers of animal bones may have been connected to the glove trade as not all glovers brought in leather. In 1848 Eliza Buffham was found guilty of assaulting Ann Richardson, a servant, in the street. The full history of the “ancient thatched cottages” is unclear but connections to general criminal behaviour seem likely.

The Stags Head

When the skeletons were unearthed at The Hornes stables in 1878 the time of their burial was thought to be around seventy years before. These stables had been erected in the early 1800s, reportedly the position of the remains led to the conclusion that they could only have been placed there after the completion of the building. In November 1805 The Stags Head Inn was offered for sale, there was no mention of newly built stables in the advert.

An interesting new occupant arrived in the first ten years of the century but situation of the previous owner also appears complex. Interested parties were informed that they would be show around by Martin Wilkinson, tennant ( the father of our 19th century storyteller). The owner of the premises being a Grimsby man, Richard Fishwick. This seemed a curious situation. Richard Fishwick was a successful draper in Grimsby, he was 25 years old and about to marry Mary Ann Mumby of Stallingborough.

Richard Fishwick was born in Belleau baptised in September 1779, his father had died before he was two years old. Richard senior, husband of Susanna, was born in Belleau in 1722 and is buried there along with three of their children, all of whom died in infancy. 18 months later in February 1783 Susanna Fishwick, widow, married Robert Harrison of Gayton and the couple settled in Saltfleet. It is unclear how the Stag’s head came to be in the ownership of Richard Fishwick (Jnr), it may have been that the premises and associated land were inherited from his father. Robert Harrison may have looked after the premises for his step son, or a local solicitor may have overseen the premises.

The connections with Saltfleet and Belleau are interesting here raising more possibilities for links with free trade. That said Belleau history reveals ties in land ownership with Salfleet too. Labourers could easily have worked between the two areas on the same estate.

In 1807 Samuel Stephenson first appears as a licensee in Alford, the new landlord of the Stag’s Head Inn, his surity was provided by Thomas Frow. The same Thomas Frow who stood witness at a Wilyman wedding. In 1812 Richard Fishwick died at the age of 32, on 12th March 1813 a land sale confirms that he owned land at Thoresthorpe, the occupant when sold was Samuel Stephenson.

Samuel Stephenson remained landlord of at the Stag’s Head until his death in 1850. The name is a common one which has caused great difficulty in tracking down his roots and connections. An 1835 poll book confirms that he actually owned the premises from that point at least.

As yet little else is known about Samuel Stephenson and his wife Jane apart from an intriguing diary entry by Alford diarist Robert Mason when they died. The couple passed away within a few days of each other and received the customary entry in Mason’s diary:

The above pair had lived together near fifty years, without God and, without hope in the world, and died in the same condition. When advised in his dying moment to sue for mercy he exclaimed it is too late and cursed and swore almost to the last. I never saw either of them at a place of divine worship in my life.

They had accumulated a considerable portion of this world’s goods. He had an awful end, crying take that great man from my bedstead.

Robert Mason’s diary entry was 28 years before the skeletons were found. It does open up the possibility that Samuel Stephenson was aware of those bodies buried in his stable for years.

Interestingly prior to 1846 Samuel Stephenson’s son held tenure of an “old established and well accustomed coal yard, house and premises lying close to the opening at the shore in Chapel. Alford trade directories include Samuel Stephenson (Jnr), ironmonger and coal merchant in Alford. Clearly carts were bringing coal from that gap into Alford.

The Three Tuns

One other old inn which is deserving of attention in connection to the skeletons is the Three Tuns.

Various landlords of the Three Tuns Inn appear among early Alford licensees in quarter sessions documents from 1792 to 1828. Trade directories list the inn and associated landlords until 1842. The Buffham family are not associated with the Three Tuns in any of these records. The tavern stood in the Butter Market, a location label which was applied to Buffham’s old cottages, the exact boundaries of this market area are unclear.

Auction details in 1819 show the Three Tuns was a large premises. At that time, the property included a brew house, stable, granary and other outbuildings. Through the 1820s and 30s this tavern was in the hands of a horse dealer but also continued to trade as the Three Tuns.

When considering the market place area it is hard to rid ourselves of the existing buildings. It is possible that this premises covered part of the area now cobbled. It may have been connected to Buffham’s cottages, or they may have inhabited part of it in the 1840s. Skeletons were found beneath Buffham’s cottages(1868) beneath the phone boxes, now seating (1949) and reportedly when excavating around the fountain.

The area around Buffham’s cottages was the site of many improvements from the 1840s onwards. The stocks and an old prison had been located in this area for decades. The lock up in Occupation Road was not agreed upon until 1844. There are a lot of unknowns which could have a factor on the skeletons in this area. The markets and fairs attracted a lot of farmers, dealers and hardened criminals to the inns, not all of them made it home.

Part 6 : Smuggling Times in Alford – The Poor

Harsh Reality

In 1788 a few days before Christmas, a labourer’s wife from Willoughby, stole a pound of candles from a local store. The goods were worth 6d, the young man in charge was not sure what to do but at the insistence of a local farmer’s wife the culprit was charged.

Nelly Coupland spent Christmas in Louth House of Correction waiting for her case to be heard. On 13th Jan. 1789 she was found guilty at Spilsby her sentence was as follows:

… to be recommitted to the House of Correction at Louth till Monday 16th February next, to be then brought to Spilsby, the next day taken to Alford and there publickly whipt from the prison round the sheep market to the church yard gate, and from thence to the water and back again to the prison through the Market Place and there discharged Bill Painter LNALS Louth House of Correction

Nelly was to be humiliated, whipped while she was walked through the town on Market day. 18th c. punishments were victim led, those convicted were shamed for public spectacle. Despite living within the parish of the Reverend Gideon Bouyer Nelly Coupland could not be protected from the law of the land.

The Parish Workhouse

Life was not much better for the poor who remained within the law, the old and infirm, children too young to work, all ended up in the parish workhouse.

A survey of the poor in 1791 recorded 188 families living in Alford consisting of tradesmen, common mechanics, shopkeepers, farmers, a few labourers and innkeepers for the 11 alehouses. The poor were maintained in a parish workhouse run by a paid governor. In 1791 Fifteen inhabitants were recorded; three children under 7 years of age and three between 7 and 15, the remaining inhabitants were simply declared old.

The report stated “The house is poorly run by an old lady who is virtually a pauper and unable to maintain good order or industry” …neither was the “neatness which discovers itself in some workhouses to be found here”

In reality those capable of earning money by industry did so beyond the reach of parish officials.

Alford: Early 19th Century

Over fifty years on from the first Lincolnshire Stuff Ball Alford remained in the grip of poverty and crime. Demobilisation at the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815 released between 250,000 and 400,000 into the labour market nationally. Corn prices dropped, labour rates fell by around a third and the demand for labour was in decline as the additional work created by enclosure was coming to an end. The effects of enclosure remained, the population was increasing but labourer’s housing was diminishing. In 1832 the Reverend E Dawson of Alford wrote at length on the Causes of Pauperism for the Labourer’s Friend Society, directly substantiating his work with facts and figures from Alford and the surrounding parishes. Dawson closed his paper with the words …

I cannot but conclude, that … [just] as the demolition of cottages with land … has produced a great increase of pauperism, so pauperism has produced a great increase of crime .

The punishments for those stepping over the line continued to be harsh. In October 1839 John Wood (40) and Harriet Wood (15) were found guilty of theft from William Wilson, druggist, of Alford. The pair stole a quantity of tobacco, a hymn book and other articles. John Wood was sentenced to 2 months in Louth House of Correction with hard labour. Harriet received 6 months in Spilsby House of Correction with hard labour.

William Wilson was under pressure form various angles, in January 1843 he was the petitioner against bankrupt Thomas Charles Clarkson, a tanner of Lambeth. It appears that Mr Wilson had business contacts a long way beyond the boundaries of Alford.

Part 7: A Tangible Proof ?

Men of Influence : Men of good standing ?

The harsh realities of life in the Alford area, the opportunities provided by the nearby coast and the fear of the workhouse explain why many would become embroiled in the smuggling operations. The question remains who were the men controlling and organising the trade locally. A couple of events in the 1840s do provide information on one Alford man in particular.

On 27th September 1844 a large seizure of tobacco was made by the Excise on the premises of Messrs Garton, tobacconists, of Lincoln. They seized 720lbs of foreign tobacco. The bales had been landed on the Lincolnshire coast and made their way across the country by way of Horncastle to Lincoln. The Hull Advertiser reported that “they were brought by carrier and, after lying at a public house for some hours, placed in a cart in the midst of market day to be conveyed to Messrs Garton’s premises. Immediately the gates of the manufactory were thrown open, and the cart backed in, the seizure was made. Penalties were estimated to be nearly £400.

T and R Garton swiftly responded to the press reports writing to the Hull Advertiser the following week. They emphasised that the cart had arrived without their knowledge and they had nothing to do with the transaction. Furthermore they had found out since that ” the plot and conspiracy were laid by parties , one of whom is a druggist not 100 miles from Alford, the other two are ex-tradesmen well known in Horncastle and Louth and well known to the board of Excise. Two of them are exchequered under heavy penalties. It is strange that the board allow these worthies to go at large pursuing their collusive practises, namely to smuggle on the one hand and inform on the other. Inviegling unsuspecting people into their meshes for the purpose of victimising them out of their money and for an excise officer to lend himself to carry out their views [in order] to share in the fines is against the spirit of the rules laid down for his duty.

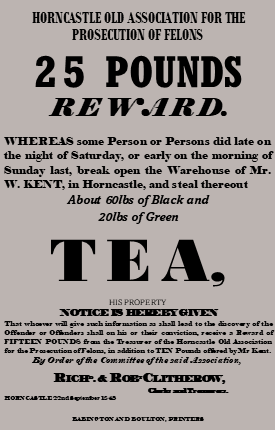

One year later the Horncastle Old Association for the Prosecution of Felons offered a 25 pounds reward for information leading to the conviction of those involved in a Tea robbery in Horncastle. 60lbs of black tea and 20lbs of green tea were stolen from Kent’s Warehouse. Privately the association wrote to Superintendent Casey at Alford and requested that a watch be put on two Alford men the parties having been suspected, for some time, of stealing tobacco. The party who conveys the goods away is no doubt your carrier Elvin. The party to whom they are sold is thought to be William Wilson, druggist of Alford. Despite lengthy surveillance the parties were not caught. Ironically the matter continued to rumble on into early 1846 when the Horncastle Association refused to pay the bill for the watch and Henry Titus Bourne put them in court for the non -payment of the bill.

Unlike the Woods family, who stole from his shop, William Wilson was not convicted, he may have had more influential friends. William Wilson provides the first tangible link to the men of influence in Alford who were involved in the trade, he was born in Grimsby in 1811, the son of an innkeeper, research continues but I suspect that Robert Roberts was quite right, everybody knew it !

Snippets of more Alford Smuggling stories appear below: